Archaeologist Jennifer McCarthy writes about her research, which draws significantly on the Transport Infrastructure Ireland Digital Heritage Collection in DRI

The author of the below blog post, field archaeologist Jennifer McCarthy (pictured, left, with DRI Director Natalie Harrower), is the winner of the inaugural DRI Early Career Research Award.

The following article discusses research undertaken as part of a thesis completed in partial fulfilment of a master’s degree in Archaeological Excavation. The research was supervised by Professor William O’Brien of the Archaeology Department at University College Cork during the academic year 2016–2017. The research focused on the reinterpretation of a Middle to Late Bronze Age settlement site uncovered during site investigation works prior to the construction of the Youghal Bypass, Co. Cork in the early 2000s. Such a task relied exclusively upon uncovering regional trends to support a reinterpretation. Access had to be gained to an extensive archive of previous archaeological excavation reports from comparable large-scale road infrastructural projects, which was made possible during the summer of 2017 by the Digital Repository of Ireland (DRI) website.

‘The height of commercial archaeology in Ireland occurred in the early 2000s under the remit of the National Development Plan 2000–2006’

The height of commercial archaeology in Ireland occurred in the early 2000s under the remit of the National Development Plan 2000–2006, in which the Irish government set out an ambitious plan for public investment in the Irish economy over a seven-year period (Hanley and Hurley 2013). Under this plan, over 100 major road projects were scheduled, an undertaking unparalleled since the formation of the state (ibid). This investment led to one of the most intense and unprecedented periods of archaeological investigations ever undertaken in Ireland (ibid). The result was a deluge of new discoveries preceding the development of each new road, which drastically changed the course of our understanding of the past. This period in Ireland’s history, dubbed ‘the Celtic Tiger’ resulted in the lack of publication and so-called ‘grey literature’ due to private companies trying to keep up with the demand of new projects. However, a considerable effort has recently been made online by Transport Infrastructure Ireland (TII) Digital Heritage Collections, which include more than 1,500 archaeological excavation reports, representing more than 80% of all reports commissioned by the National Roads Authority and the Railway Procurement Agency (now collectively known as the TII) during Ireland’s infrastructural building programme between 2000 up to 2016.

The construction for the c. 6km Youghal Bypass began in 2001 and took nearly two years to complete. As part of the archaeological investigations prior to construction, a Middle to Late Bronze Age, low-order domestic farmstead known as Ballyvergan West 1, and associated artefacts consisting primarily of farming tools were discovered. Amongst the discoveries was the tokenistic (partial deposition, commonly between 15–30% in this period) cremated human remains of one individual dispersed amongst several shallow pits. The excavation director interpreted such an act as ‘rubbish’ primarily due to the accompaniment of mundane material culture including several sherds of Bronze Age coarseware pottery, debitage (lithic working waste), a whetstone and a saddle quern within these pits (Kehoe and O’Hara 2002). The primary argument in the reinterpretation focused on the cremated human remains and the material culture as supporting evidence for ritual activity.

(Bridge over the Youghal Bypass. Photo by David Dixon, https://www.geograph.ie/photo/6054106)

‘The scope of the reinterpretation adopted a landscape perspective, aiming to view the site not as a discrete entity but rather on both a local and regional scale’

The scope of the reinterpretation adopted a landscape perspective, aiming to view the site not as a discrete entity but rather on both a local and regional scale, as no site ever existed in isolation. Interaction with the landscape was necessary for sustaining human life. Contact with other communities and groups was inevitable and, in such interactions, ideas were exchanged, and friendships were forged. Such ideas resulted in the marking of the landscape, which survives in the archaeological record today in the form of monuments, artefact finds and burials. These, collectively, can inform archaeologists about a wealth of information including lifestyle, sacred beliefs and ideologies. They, in turn, when their contemporaneity can be proved to link with such sites in proximity, can contribute greatly to the interpretation as a whole.

The central theme encompassed a presentation of a ‘ritual versus rubbish’ argument of the pits and their contents as an expression of ritual behaviour, an argument which has grown increasingly popular in recent times in prehistory. It is important to consider houses and domestic settlements in more than purely functional terms— societal conditions need to also be addressed. Several arguments have been raised to support this idea; including: the recurrent use of only token deposits of cremated human remains, the preferential choice of bones deposited and post-mortem treatment—particularly evident on Middle to Late Bronze Age settlement sites—and the use and deposition of artefacts to further argue a ritual and symbolic nature of the site.

The recurrent use of only token deposits of cremated human remains is particularly evident on Middle to late Bronze Age settlement sites and has a wide distribution in Ireland. Examples can be seen at Cloghers, Co Kerry (Kiely 2002) and Kilmurray North, Co. Wicklow (O’Neill 2001a). The very act of cremation alone indicates that human bone was recognised as important, as can be seen at Newtown, Co. Limerick (Coyne 2001), where even the smallest body parts were retrieved from the funeral pyre, indicating considerable effort (ibid). The tokenistic nature of the cremated human remains suggests that they may have burnt only selected bones for use as a symbolic representation and perhaps the remaining body parts may have been retained as ancestral relics by the living and distributed amongst the mourners or scattered (Cleary 2005). This idea would not support casual deposition.

Along with the tokenistic nature of the deposits, there is further evidence for ritualistic behaviour, with the practice of preferential choice in bone type represented. There is a preference for skull and long bone fragments, which in the settlement site under review, two contexts, C90 and C105, comprised of skull fragments and in a further two contexts, C138 and C158, consisted of long bone fragments out of a sample of seven. It is important to note that soil conditions are unlikely to account for the tokenistic human remains as studies have indicated that, primarily through changes in the chemical properties of bone during the cremation process, cremated bone tends to survive very well in most soils including acidic environments (Mays 1998, 209)—suggesting that such taphonomic processes are unlikely to account for the token nature of the deposits (Grogan et al. 2007).

(Aerial view of Caltragh Middle Bronze Age houses. Photo by Ed Danaher, https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.m9012833x)

Brück (1995, 256–7) has suggested that skull fragments may have been ‘chosen for use because of their symbolic connotations…perhaps as the seat of the intellect or soul’. The skull could also have been viewed as carrying the essence of an individual and may therefore have warranted exceptional care after death to ensure general good fortune, such as the fertility of the inhabitants and their crops (ibid). The long bones may have been viewed in an equivalent way, perhaps as holding the strength of the deceased, with the living treating them in a specific way to ensure their own health (ibid). There is a history of such a patterns occurring on contemporary settlement sites in Ireland and can be found at Chancellorsland, Co. Tipperary (Doody 2008), where four skull fragments were uncovered in the outer ditch and again, skull fragments were discovered from the outer ditch at Stamullin 10, Co. Meath (Ní Lionáin 2006). A particularly strong example of the occurrence of skull and longbone fragments may be seen at Cloghers, Co. Kerry (Kiely 2002), where out of nine contexts where human remains were present, both skull and longbones were found in seven.

Other clear post-mortem ritualistic acts include the further crushing of bone. The possibility of additional fragmentation through intentional manual crushing and pounding can be interpreted as another stage in multi-phase mortuary treatment (Cleary 2014). This can be seen at Ballyvergan West 1, where the osteoarchaeologist determined that from the seven samples obtained for further analysis, all of the cremated bone was moderately to highly crushed. This can also be witnessed at a pit burial at Rockfield, Co. Kerry dating to the Late Bronze Age (National Roads Authority/Collins).

‘Ritual activity formed an integral element in the life of Bronze Age farmsteads’

Ritual activity formed an integral element in the life of Bronze Age farmsteads and it is hardly surprising that at least some of this appears to have been concerned with agricultural fertility, in the form of the deposition of tools connected to farming (Brück and Fokkens 2013). This idea is evidenced at Ballyvergan West 1, where a saddle quern fragment was recovered from pit C138a and another possible saddle quern was recovered from pit C112a. It is possible that such pits, in which the saddle querns were deposited, represent ceremonial actions that were brought into the everyday by the inclusion of mundane objects (ibid). The presence of a saddle quern has been recorded elsewhere on a number of Middle to Late Bronze Age settlements, including Ballybrowney Lower 1, Co Cork (Hanley and Hurley 2013) (National Roads Authority/Cotter) and Ballycummin, Co. Limerick (Gahan 1998).

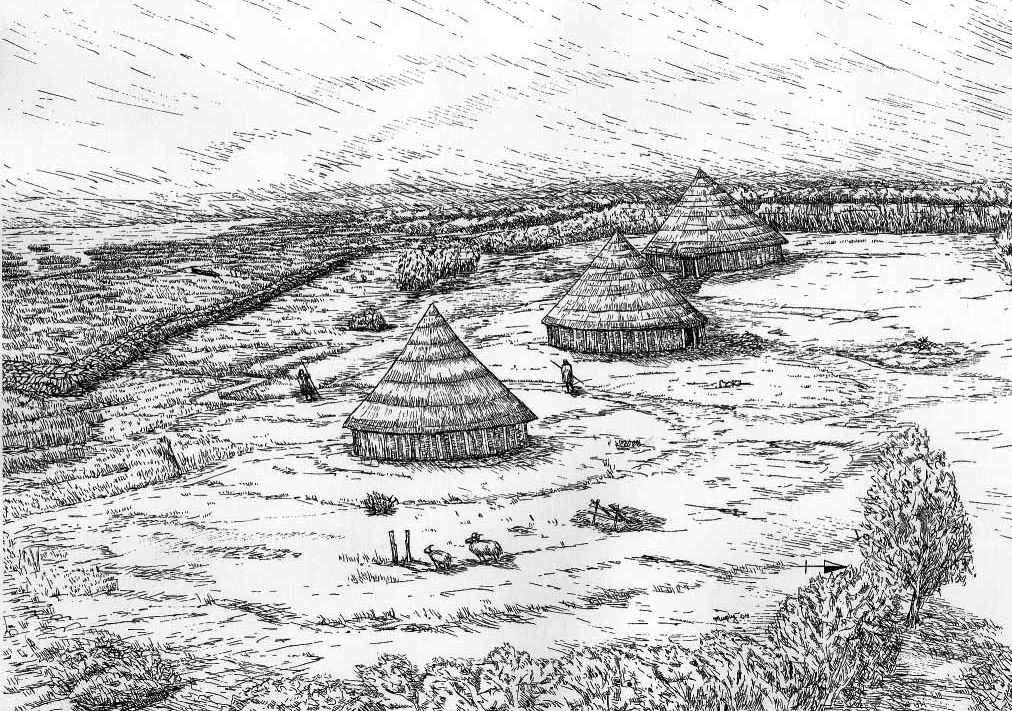

(Artistic reconstruction of the Caltragh Middle Bronze Age settlement by John Murphy, Archaeological Consultancy Services Ltd, https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.m9012833x)

The inclusion of the saddle quern may have symbolised fertility in crops. When combined with the human remains from the site, it may be seen as related to fertility in females and prosperity in social relations (Brück and Fokkens 2013), as present at Ballyvergan West 1, in pit C138a. This argument may be developed further, as in the same pit context, there were also the remnants of possible mudstone debitage and domestic coarseware pottery present. An example of a comparable find may be found at Caltragh, Co. Sligo, where the cremation was accompanied with flint scraper and pottery sherds (MacDonagh). When these finds are all woven together, this further strengthens the fertility theme. The coarseware pottery was of domestic nature and was more than likely used to hold and store food items to sustain the inhabitants. The mudstone debitage may be interpreted as a link to tools connected to farming, as the debitage was a by-product of stone tool manufacture that may be linked to farming.

The evidence in the reinterpretation of Ballyvergan West 1 focuses primarily on the presence of the cremated human remains, which is further emphasised by their tokenistic nature and post-mortem treatment. The artefacts deposited both within and amongst the human remains may have held potent symbolism, which varied depending on what was deposited and in what context they were found. It has been argued here that the very presence of cremated human remains and the effort that went into the process of cremation, is significant in its own right, for there is no other instance where the living and the dead were closer. The arguments presented in favour of a reinterpretation provide strong evidence-based support in the form of undercovering local and regional trends of comparable sites.

‘Resources like the Digital Repository of Ireland … pave the way for open source material to be shared and used’

Archaeological data and interpretation are, by their very nature, fragile due to their bias of being primarily dependant on the economy and associated infrastructural projects to enable archaeologists to uncover new sites. Due to the sensitivity of archaeological data, any one site has the power to alter our understanding greatly of any given time period. For this reason, dissemination of final excavation reports is critical to the discipline, enabling researchers to continually develop and explore new possibilities. Resources like the Digital Repository of Ireland enable just this and pave the way for open source material to be shared and used.

– Jennifer McCarthy BA, MA, MIAI

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor William O’Brien of the archaeology department of University College Cork for his unwavering support and guidance throughout not only my postgraduate studies but also undergraduate. I would also like to thank my mentor, Julianna O’Donoghue of Mizen Archaeology for her continued support and encouragement. A thanks also to Dr. Deborah Thorpe of the DRI for her kind comments and text editing and also a thanks to Dr Natalie Harrower and to the rest of the team at the DRI.

Bibliography

Brück, J. and Fokkens, H. ‘Bronze Age settlements.’ The Oxford handbook of the European Bronze Age, edited by H. Fokkens and A. Harding, A. Oxford University Press, 2013, 82–101.

Brück, J. 1995. A place for the dead: the role of human remains in Late Bronze Age Britain. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 65, 145–66.

Cleary, K. 2005. The dead amongst the living on Irish Bronze Age settlements. The Journal of Irish Archaeology 14, 23–45.

Doody, M. G. The Ballyhoura hills project. Discovery programme monograph 7. Wordwell, 2008.

Gahan, A. 2000. ‘Ballycummin.’ Excavations 1998: summary accounts of archaeological excavations in Ireland, edited by I. Bennett. Wordwell, 200, 129.

Grogan, E. O’Donnell, L. Johnston, P. and Gowen, M. The Bronze Age landscapes of the pipeline to the west: an integrated archaeological and environmental assessment. Wordwell, 2007.

Hanley, H. and Hurley, M. F. Generations: the archaeology of five national road schemes in County Cork. National Roads Authority scheme monographs 13, 2013.

Kehoe, H. and O’Hara, R. Report on the archaeological resolution of features exposed at Ballyvergan West, Youghal bypass, Co. Cork. Archaeological Consultancy Services Limited, 2002.

Kiely, J. ‘Cloghers, Tralee’. Excavations 2000, summary accounts of archaeological excavations in Ireland, edited by I. Bennett, I. (eds.). Wordwell, 2002.

MacDonagh, M. Valley bottom and hilltop: 6,000 years of settlement along the route of the N4 Sligo Inner Relief Road by Michael MacDonagh, Digital Repository of Ireland [Distributor], Transport Infrastructure Ireland (TII) [Depositing Institution], https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.m9012833x

Mays, S. The archaeology of human bones. Routledge, 1998.

National Roads Authority, Transport Infrastructure Ireland, & Coyne, F. Archaeological excavation report, 01E0214 Newtown, County Limerick, Digital Repository of Ireland [Distributor], Transport Infrastructure Ireland (TII) [Depositing Institution], https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.cv442b57m

National Roads Authority, Transport Infrastructure Ireland, & Cotter, E. Archaeological excavation report, 03E1058 Ballybrowney Lower 1, County Cork, Digital Repository of Ireland [Distributor], Transport Infrastructure Ireland (TII) [Depositing Institution], https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.ws85pw53v

National Roads Authority, Transport Infrastructure Ireland, & Collins, T. Archaeological excavation report, 99E0323 Rockfield Kerry, County Kerry, Digital Repository of Ireland [Distributor], Transport Infrastructure Ireland (TII) [Depositing Institution], https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.ww72qs401

Ní Lionáin, C. 2006. Stamullin, Meath. Available [Online]: http://www.excavations.ie/report/2006/Meath/0016393/ [Accessed 26 July 2017].

O’Neill, J. 2001a. Excavation of a Bronze Age house in Kilmurry North, Co. Wicklow. Margaret Gowen and Co. Ltd. Available [Online]: www.mglarc.com/proj ects/kilmurry north.htm. [Accessed 1 August 2017].00